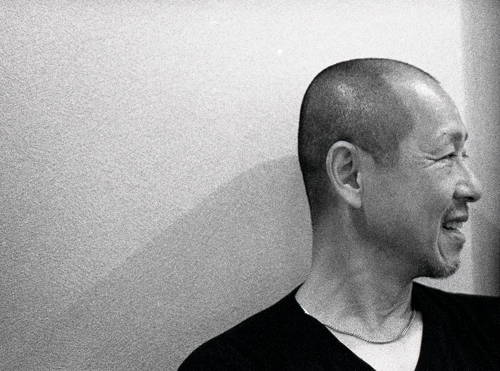

Minagawa Tsukasa 皆川司

|

Respect is simply earned. Power is more complex and accrues to certain individuals in mysterious ways. Minagawa Tsukasa is proof. He doesn’t wield money– he almost eschews it. He hasn’t inherited any rank or title. Power through fear? There are of course reasons you wouldn’t want to cross him, but fear isn’t the mode by which he generally operates. Even when I remark to him that many people in Kyoto consider him powerful, he smiles and shakes his head. “I’ve got no influence. But I do have many friends.” The friends of his that I’ve met seem like honest, hard-working people: a tofu maker, restaurant staff. One night after leaving a restaurant in Kyoto with him, a taxi driver stops, opens his door and says, “Minagawa-san! Jump in– I’ll give you a free ride somewhere.” He thanks the man, but declines the offer. Like all powerful individuals, many people he doesn’t know, know him. And the influence he says he doesn’t have touches people several degrees removed from him. Minagawa is not mafia. He’s neither a politician nor spiritual leader. He’s a gardener. This was not the life he envisioned. In fact, he’s not even sure he envisioned any sort of career before he started down the path, literally, in high school. “My father ran a dry-cleaners. But a friend’s older brother was running a gardening business so I started working part-time with him. After graduating, I continued with that, apprenticing from age 18 to 20. At first, I didn’t think I was going to be doing this my whole life. “When I was about 20, I went to work for a patisserie. I eventually realized that working like a robot inside a room wasn’t for me, so I went back to working in gardens. I got married at 23 and realized I had to do something with my life; I had to decide.” Minagawa was, at the time, working with a well-known gardener in Kyoto. It took about another year before it began to sink in that this would be his life’s work. By 24, he had already learned much by way of technique. But gardening, especially in Japan, has layers of knowledge and tradition. “Knowing botany and the characteristics of the many plants used in gardens is not enough. You have to understand rocks and the many components of a Japanese garden made of rocks. First you have all the landscaping stones. Then you have toro (stone lanterns), stone pots, stepping stones, even the fine gravel paths commonly used at shrines—that we smash up using hand mallets and a special mixture of materials. “After that, you have to study things like takegaki (bamboo fences) and even carpentry if you are making mon (gateways). You also have to study tea ceremony, I think, to understand what kind of gardens or courtyards would be appropriate to that tradition.” How long does it take to learn all this? “I’m still learning,” says Minagawa, over three decades after he started this work. And what are you best at? “Arranging rocks. And taki no iwagumi (waterfalls cascading over rocks). I’d say design,” after which Minagawa is quick to differentiate between design and technique in his line of work, where design is the vision and planning, technique is the execution. I watch him for a while at his technique while he and his team are grooming the grounds of the International House in Roppongi. It’s a week-long job and Minagawa and his team of about five other gardeners, including his son, have driven up from Kyoto. “I hope this branches out,” mumbles Minagawa as he trims backs some azaleas, “or it’s going to look bald like me.” He and his team trim quickly, seemingly without an abundance of attention. It’s not at all like many people imagine: gardeners immersed deeply in Zen-like concentration. Instead, they trade banter and seem in good spirits in the warm, early Spring weather. Occasionally, Minagawa scolds or cautions someone. Have you ever screwed up? “No,” he quickly replies, “but sometimes there are differences in what I want to create and what, for example, the priest of some temple wants me to create. And I’m also careful. If I have a young helper without the best sense of form or aesthetics, I might not use him so much.” Maintenance of temple and shrine gardens is a regular job, but the actual creation of one is very rare. Even complete overhauls of established gardens are unusual. Minagawa has worked at some rather hallowed gardens, the names of which he doesn’t want mentioned in any article on him, out of a sense of humility. So how does one go about getting such work? “I hate doing sales,” says Minagawa, “There are other gardeners in Kyoto who really work hard at doing sales, but I’ve worked my way here entirely through introductions from friends. I’m not so interested in the money. I love the culture and history of Kyoto. I want to see that passed on and my job is a part of that. I make sure that youth I work with understand the history and culture behind this job, so that doesn’t disappear.” People in Kyoto and beyond no doubt respect that. He talks to me about some temple priests that have called him in to advise on the design of a new garden which his colleague will actually build. He says he doesn’t want to be involved in the hands-on side of the work because he wants it to be his colleague’s individual work of art. Which gardeners does he respect? “Kobori Enshu. That guy, in that era, did some amazing work. There was a psychological element to his gardens that’s incredible.” Minagawa’s hands are visibly strong, but not from gardening alone. One night he mentions that he does karate so I square off with him. He becomes light on his toes, like Muhammed Ali’s famous “dance like a butterfly” line, and loose with his arms as he pulls up his guard. He throws a few shadow punches—blink and you miss them—which pop millimeters from my chin. We’ve been drinking and I’m glad he doesn’t miss. Minagawa has been practicing shotokanryu for over 40 years and runs his own small dojo. “Karate is my mental training.” Minagawa is also an avid participant in local festivals, where he is one of the designated few that gets to shoulder the floats. Word is that he’s very passionate about this and that others are careful not to screw up, as much out of fear of displeasing Minagawa as out of concern for upholding tradition. “I’ve been hoisting floats in festivals, including the big one in Gion, for twenty years now. I was invited through work connections.” While Minagawa has benefited his whole life from such connections, he also uses his own to help others. He’s a fixer, connecting appropriate parties in important ways, and perhaps therein resides his power. He’s a gatekeeper as much as a physical gate maker. In Kyoto, where the outcome of many decisions often depend on the nods of individuals in the shadows, being in Minagawa’s good graces does not hurt one’s cause. In the end, for Minagawa, everything comes back to gardening, not power. “In my free time, I like to admire works of art made out of stone. I like to go view old toro, ask about where the rock came from, when they were built, what influenced the shape. I like to appreciate the texture of the rock.” “I have a very small garden at home with four toro. The foundation stone for one is ancient, dating back to the Asuka Period (592-710).” He smiles and I wait for the rest of the story, but there isn’t one. He’s nodding distantly, as if imagining that stone in his head. It’s an appropriate piece of a garden for him to be proud of. And most people never notice it. |

尊敬に値する人は尊敬されるべくして尊敬されるものだが、人を動かす力というものはもっと複雑で、誰がどれくらい人を動かせる力を持っているかはなかなか分かりにくいもの。皆川司の場合もそうである。 彼はお金に執着しない。それどころかお金が嫌いなのでは?とさえ思える。親から社会的地位や肩書を受け継いでもいない。怖そうに見えるから周りが気を使っているのか?確かに、誰も彼に逆らおうなどとは思わないだろうが、しかし彼が恐怖心を利用しているとは思えない。皆川は人を動かす力があると皆に思われているという事実を指摘したときも、彼は笑顔を見せながら首を振って否定した。 「私は影響力なんて持っていません。友達が多いのは事実ですが」。 私が会った彼の友人たち、豆腐屋と食堂の従業員はどちらも正直で勤勉なタイプだった。ある夜、僕は彼と一緒に京都市内の食堂を出たところで一台のタクシーが目の前に停車したと思ったら運転手が後部座席の自動ドアを開けて言った。「皆川さんじゃないですか!乗ってください。タダで行きますから」。皆川は運転手に礼を言いながら、丁重にその申し出を断った。 彼が知らない人でも向こうは彼のことを知っている。本人は「持っていない」と言う「影響力」が彼と立場の異なる人々を動かしている。しかし皆川はヤクザでもなんでもない。政治家でもなければ教祖でもない。 彼の正体は庭師である。 庭師になりたくてなったわけでもないという。高校生の時にこの道に足を踏み入れるまでは特に何になりたいという考えさえ持っていなかった。 「実家はクリーニング店など何店舗かを営んでいたのですが、高校の友人のお兄さんが庭関係の仕事をしていて、私はそこでバイトを始めることになりました。高校卒業後もそのバイトは続き、18歳から20歳までは見習いとして働きました。最初の頃は一生続けることなど考えていませんでした。20歳の頃ケーキ屋で働き始めたのですが、そこで気付いたことは、屋内で機械的な作業をする仕事は自分に向いていないということでした。それで、以前の庭関係の仕事に戻ることにしました。その後23歳のときに結婚して、人生を真剣に考えるようになりました。決断の時でした」。 皆川が当時働いていたところは京都でよく知られた造園業者だった。庭師を生涯の仕事にしようと決心がつくのにさらに一年を要した。技術についての修行を積み、24歳になった頃に独立した。しかし庭師の仕事は、特に日本の場合、知識と伝統の奥が深い。 「植物の生態を知り、いろいろな植木の特徴を学んだとしてもそれではまだ不十分です。石の特性も勉強し、日本の庭の重要な構成要素となる様々な石造物について学ぶことも大変重要です。景石だけでも色々あるのです。さらに灯篭、石鉢、踏み石、寺社でよく見る砂利道、などです。細かい砂利は槌で砕いて作ります。そういったことを全て勉強してもまだ他にもあります。竹垣についても知らなければなりませんし、庭に門を設置しようと思えば大工仕事の領域もカバーせねばなりません。場合によっては茶道についての知識も必要になります」。 一通り習得するのにどのくらいの年数がかかるものなのだろう? 30年以上この仕事に携わってきた皆川でさえ、この質問に対する答えは「今もまだ修行中です」というものだった。 得意分野は? 「庭石、特に滝の岩組(石で組まれた滝)でしょうか。そういった構造物をデザインするのが得意です」。そう言いながら皆川はデザインと技術の違いを説明してくれた。デザインにおいては想像力と設計力が大切で、技術が重要になるのは実際の施行段階の話だという。 皆川のチームが六本木にある国際文化会館の庭園を手際よく均すのを観察したのだが、聞いた話ではそれには一週間かかり、皆川と彼の息子を含む5名の庭師チームは、遠路はるばる京都から出張に来ていたのだ。 「このツツジは枝葉がもっと伸びてくると良いのですが。このままでは私の禿げ頭みたいですから」。ツツジを手入れしながら皆川はボソッとジョークを言った。 仕事上で大きな失敗の経験はあるのだろうか。 「ありません」と彼は即座にきっぱりと答えた。「依頼主の寺の住職が私に期待する内容と、私の実際の考えが異なることはありえますが。私はもともと慎重な性格ですし、例えば助手が若くて未熟な場合は仕事を任せきりにはしません」。 境内の庭の維持管理の仕事は多いものの、実際に境内の庭園を一から造り上げるような仕事は滅多に無いという。すでに出来上がっている庭園全体を徹底的に手入れするような依頼も稀だという。皆川は誰もが知る寺社の庭園をいくつか手掛けたが、彼は謙虚にもそれらを明かすことはなかった。 そのような大きな仕事は、どうやって受けるのだろう? 「自分から売り込みに行くのは性に合いません。売り込みに熱心な同業者が京都にはいくつかありますが、私の場合は知人の紹介だけで今まで地道にやってきました。お金に対する執着心があまり無いのでしょう。私は京都の文化と歴史が大好きです。そういったものを見聞きすることが好きですし、それに関わる仕事がしたいのです。一緒に働いている若手達には京都の歴史・文化を十分に理解したうえでこの仕事に取り組むように教育しています。そういう意識を常に持ってやっていれば自然に仕事は回ってきます」。 京都の住民だけでなく、誰もが京都の文化と歴史の重要さは知っている。皆川の同業他社が手掛ける予定の新しい庭園のデザインについて、ある寺の住職が皆川にアドバイスを求めてきているという。しかし皆川はその新しい庭園はその業者独自の芸術作品となるべきものだ、という見解から、細かく具体的に意見を述べることには気が進まないという。 尊敬する庭師は? 「小堀遠州(安土桃山—江戸時代前期)です。彼の作風は心理的要素を重視していて、それは実に見事な出来なのです」。 皆川の手は見るからに強健そうだがそれは庭の仕事だけから来ているわけではない。実は空手もやっているというのでちょっと対戦してみた。彼の俊敏なつま先の動きを見るとモハメド・アリの有名な「蝶のように舞い、蜂のように刺す」動きを思い出した。脇を固める時もリラックスした腕の動きを見せ、パンチは目にも止まらぬ速さで彼の拳は私のあごの数ミリ手前で止まった。私たち二人ともアルコールが入った状態だったが、彼のパンチは正確で私の直前で止まってくれた。皆川はもう40年以上も松濤館流の空手をやっていて、彼自身小さな道場も持っているという。「空手は精神鍛錬です」。 皆川は地元京都の祭事にも熱心で、御輿の担ぎ手として参加している。他の担ぎ手たちは伝統を守ることに注意を払い、同時に皆川の祭事への情熱を削がないことにも気を配りながら、共に祭事に参加しているという。 「京都祇園祭などの大きな祭りでも御輿を担いでいます。もう20年になります。仕事関係の知人から話が来たのがきっかけでした」。 皆川は豊かな人間関係のお陰で充実した人生を歩んできたが、その顔の広さで他人の手助けをすることもある。そうした場面では重要なまとめ役としての能力を発揮するが、図らずも彼が持つ「影響力」がそこで働いていることは間違いない。仕事では実際に門をこしらえる立場であり、その他の場面では重要な「門番」のような役割を果たす。京都という古い土地柄では様々な意思決定が影の実力者によって左右されることもしばしばだが、周囲に対する皆川の温かい気持ちは誰の感情も傷つけることが無い。 皆川が重要だと思っているのはあくまでも庭師としての仕事であり、「影響力」ではない。 「余暇には、石造美術品を眺めるのが好きです。古い灯篭を見に出掛けたり、その灯篭を造っている石の出所や造られた年代について尋ねたり、その形状がどこから影響を受けているのかを調べたりします。石の質感が好きですね。我が家の庭は小さいのですが灯篭が四つあります。ある灯篭の礎石は大変古く、飛鳥時代(592-710)のものです」。 彼は笑顔でそう話し、私はその話の続きを期待した。しかし続きは無かった。彼は頭の中にその飛鳥時代の石があると想像するかのように微かに頷いた。小さいながらも彼にとっては自慢の庭なのだ。殆どの人はその石の真の価値に気付かないかもしれないのだが。 |