Tenryu-Oku-Mikawa Quasi-National Park 鳳来寺山と湯谷温泉

by Daniel Simmons

|

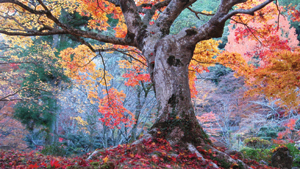

Thirteen centuries ago, long before the advent of cable car ropeways and bullet trains, travelers to Japanese hot springs were often forced to endure long walks into the lonely wilderness in order to reach their final destinations, where they could finally unshoulder their heavy loads and ease their weary muscles in volcano-fed streams. According to local legend, one particular peak-dwelling hermit in the Tokai region decided this mode of travel wasn’t for him, so he reached his favorite hot spring the easy way. He levitated. Playing a midflight medley on his flute, his robes flapping around him, the sage Rishu swooped down from the 684m-high Mt. Horaiji to a hot spring source near the Ure River, where his periodic dips attracted the attention of the locals and inspired them to open a bath there, in hopes of being granted similar magical or miraculous powers. (No dice, alas.) Flying, flute-playing mountain hermits are in short supply in Yuya these days, but this is a place where the supernatural still lingers, if you believe the claim that the local birds (Japanese scops owls) chant paeans to Buddhism in the late spring and summer: “Bu!” (Buddha), “Po!” (sutra), and “So!” (priest).  For us, the magic of this area is not in the water or the hooting of the owls, but in the magnificent surroundings. A stone staircase winds up Mt. Horaiji through an ancient wood of cryptomeria pines, cedars, and cypresses, the slopes studded on either side with moss-speckled stone lanterns and weather-scarred Buddhist statues. If you manage to ascend all 1,425 steps to the main hall of Horaiji, the Shingon sect temple that Rishu founded in 703, you’ll be rewarded with gorgeous panoramic views of the forested hills and plains stretching away below you, and on a clear day you can see all the way to Mikawa Bay. (Alas, the Horaiji temple buildings themselves lack the wabi appeal of their surroundings, having been restored and/or rebuilt numerous times over the centuries.) Here too is a Tosho-gu Shrine built in the 17th century by the shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu. This area is special to the Tokugawa family, as it is said that Tokugawa Ieyasu’s mother conceived her son after praying here. Five kilometers from the mountain is Yuya Onsen, a popular resort in the 18th century that has managed to retain a rustic, undeveloped charm. You’ll find no pachinko parlors here, just a clutch of hot spring ryokans, elderly painters practicing their watercolors by the riverside, and a beautiful prefectural park within easy walking distance of JR Yuya Onsen station. Starting in early November, the forests of the Aichi Kenmin no Mori start to blush a deep crimson and vibrant gold, offering prismatic autumnal backdrops to nature walks. If you’re disappointed with the medicinal properties of Yuya Onsen’s water (other than sodium chloride, there’s not much else in the way of extra ingredients), you can get your health fix with a stay at the beautiful Hazuki ryokan, where a master chef from Shanghai has designed a kampo-yakuzen kaiseki menu based on Chinese traditional medicine (“Dragon’s Blood” cocktail, anyone?) that will leave you refreshed and restored, and also a little weirded out. If a night at Hazuki is beyond your budget, there’s an abundance of campsites in this area. The Youth Travel Village at the base of Mt. Horaiji offers tents and bungalows, as well as auto camping sites. Closer to the Yuya Onsen station, the Kenmin no Mori campground is also a good option. Day trippers to the area can prowl the riverside accommodations in Yuya in search of an afternoon bath, and if all else fails a free public footbath in the area will put a spring in your step… if not, perhaps, enough of a spring to let you take to the skies a la Rishu. Getting There: From Toyohashi Station, southeast of Nagoya on the Tokaido main line, take the JR Iida line to Yuya Onsen station (about 70 minutes by local train, or 46 minutes on the Inaji limited express). For Horaiji, exit at Honnagashino station instead, then board the annoyingly infrequent Toyotetsu bus to either the Horaiji stop (an easy 15-minute walk to the temple) or the village at the base of the Horaiji staircase. (We recommend getting off at the bottom and earning your return ride with a bit of exercise.) |

およそ1300年前、ロープウェイも新幹線ももちろん無い時代の旅人たちは目的地の温泉にたどり着くまで大変だったろう。一人寂しく原野を何日もさまよい歩いて温泉地にたどり着き、そこでやっと重い荷物を肩から下ろし、疲れた身体を湯で癒した。東海地方には、もっと楽に大好きな温泉に行きたいと考えた仙人がいて、彼は空を飛んで温泉に行っていたという伝説がある。 尺八を奏で、服を風にはためかせながら利修仙人は標高684mの鳳来寺山から空を飛び、宇連川近くの源泉に着いた。その後もたびたびこの源泉を訪れて優れた健康と長寿を得たことに付近の住民が注目し、その不思議な湯の効能にあやかろうとの願いから湯谷温泉は開湯したという。残念ながら地元住民たちは308歳の長寿を全うした利修仙人のような長寿を手に入れることは出来なかったが。 今日では湯谷温泉にも空飛ぶ仙人は居なくなったが、超自然的なパワーは健在。鳳来寺山に住む「コノハズク」という種類のフクロウは「ブッ・ポウ・ソウ」(仏法僧)と鳴くという。 しかし僕らにとってここの本当の魅力はフクロウの鳴き声では無く、周囲の壮大な景色だ。鳳来寺山の山麓からは松、杉、ヒノキの森の中を長い石段が鳳来寺の本堂に向かって続き、石段の両側には苔の生した石灯籠と古い仏像が延々と立ち並んでいる。1425段の石段からなる参道を歩き、利修仙人が703年に創建したとされる真言宗の鳳来寺に辿り着いて下界を見下ろせば、壮大に広がるパノラマのような景色に息を飲むだろう。好天に恵まれれば三河湾も遠望できる。(何百年もの間に幾度となく改築が繰り返された結果、鳳来寺の本堂の周辺には風情を感じさせるようなものは何も残っていない)江戸時代には家光の治世で大いに栄え、17世紀に東照宮が新たに造営された。家康の生母である於大の方が鳳来寺に参籠したことによって家康を授けられたという伝説もあり、徳川家にとっては特別な場所となっている。 鳳来寺山から5kmのところにある湯谷温泉は18世紀になると人気が高まり、その素朴な味わいは素晴らしく、日本百名湯にも選ばれているほどである。周辺にはパチンコ屋なども無く、あるのは清流宇連川の流れに沿って建ち並ぶ温泉宿だけである。川のほとりには水彩画を楽しむ人もやってくる。また、JR湯谷温泉駅からほど近いところには愛知県民の森があり、宿泊施設やキャンプ場、スポーツ広場、ハイキングコースなどが整備されており、11月は紅葉も深まって、自然の中を散策するには最高の季節となる。 塩化ナトリウム以外に特に有効な成分を持たない湯谷温泉では物足りないという人には温泉宿「はづ木」に泊ってみることを勧める。上海出身のシェフが作る本場の中国漢方薬膳料理は身体も心もリセットしてくれる。安く済ませたいなら、この界隈にたくさんあるキャンプ場を利用しよう。鳳来寺山のふもとにある「鳳来寺山ろく青少年旅行村」にはテントやバンガローがあり、オートキャンプにも対応している。上述の愛知県民の森にあるキャンプ場を利用するのもいい。 清流宇連川の川沿いに建ち並ぶ温泉宿は日帰りの温泉のみ利用も可。無料の足湯もあるから、利修仙人のように空は飛べなくても気軽に湯谷温泉を訪れてみよう。  アクセス: 東海本線・豊橋駅から飯田線で湯谷温泉駅下車(普通列車で70分、特急伊那路利用で46分)。鳳来寺へは、本長篠駅前から豊鉄バス・田口新城線で鳳来寺バス停下車、徒歩15分。ただし、本数は少ない。また、鳳来寺山頂バス停へは11月の土休日のみ運行している。 |