A Voice of Reason

|

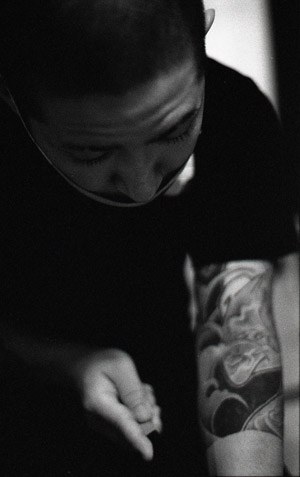

Horimyo has a bright but piercing look in his eye and gives me a firm handshake when we first meet. He brims with focused confidence, the kind that can bring life to certain possibilities. He is, it is quickly apparent, a man with a purpose. He calls it “a way.” (道) The ‘way’ for this young tattoo artisan has been twisting. He traces his roots to the influence of friends in his late teens, when he began to embrace an interest in Chicano culture via the pervading ‘gangsta’ style. Horimyo reminisces, “At the age of 19, I went to America all by myself, fully intending to seek out and learn about Chicano culture. From there I went down to Mexico and witnessed with my own eyes just how miserably poor it was. Even in L.A. you’ll find that because of the poverty gangsters will kill a man for as little as $10. I was deeply struck once again by the fact that I was Japanese. I realized that this absorption with Chicano culture and the gangsta look in a rich country like Japan isn’t real at all—it’s fake. And so I had to think, ‘What in the world would be a genuine style for someone like me?’ The importance of pride and patriotism shared by so many people in other countries occurred to me. But in Japan, which lost so much of its pride and patriotism with defeat in the war, what is there for someone like me, who is very much Japanese, to be proud of? I realized that it was traditional Japanese tattoos (irezumi), which have been appreciated and highly praised around the world. That’s what I want to convey to my generation. At least those were my thoughts there along the Mexican border.” That kind of ‘way’ would be a long, uphill battle.

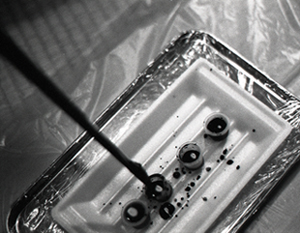

After returning to Japan, he struggled with the discrepancy between his desire for some semblance of freedom in his life and the strict hierarchy of the tattoo world. In the larger context, there was the Japanese ‘way’ of making international donations to poor countries. Caught among conflicting worlds, he found the way to becoming a tattoo artisan elusive. He fretted over his future and the days passed aimlessly. Then one day a friend showed him a book in which an article read, “The influence of Mehandi (henna tattoos), which has a history as ancient as tattoos, can even be seen in Madonna’s promotional videos, and the art is currently all the rave on America’s West Coast.” Horimyo’s first reaction was, This is it! His next reaction: a flight to L.A. Henna tattoos use traditional body paints that disappear naturally in about two or three weeks. Horimyo studied under a well-known artist there, but fate took another turn. On an airplane back home, Horimyo was seated beside a tattoo artisan who would later ink the traditional shôryû (dragon) image on the back of Horimyo’s head. Through this man’s introductions, Horimyo was able to connect with others in the tattoo world, and through their auspices, he met various tattoo artisans. Eventually, an artisan in Kanagawa prefecture who does irezumi completely by hand became his teacher. After a three-year apprenticeship under him, Horimyo went independent—that was about six and a half years ago. Rather than practice among a tightly knit group, as is common, he decided to work solely on individuals who wanted tattoos for deeply personal reasons. He carefully chose his pseudonym. “Hori” (彫) derives from tebori (手彫り), or tattooing by hand, as he eschews all use of machines in his work. “Myo” derives from myôhô (妙法), a Buddhist term literally meaning the “Mystic Law.” For Horimyo, myô is a kind of spiritual pillar central to life. Those who bear his tattoos will have their bodies inked with a part of traditional Japanese culture that has been held in high esteem around the world. With the hope that they would feel some amount of pride as Japanese and that they would live forward-looking lives, he embraced “Horimyo.” Before actually working on a tattoo, he first holds extensive meetings with his client and on the day he begins the tattoo, he spends hours in prayer and meditation. His tattoos do incorporate Buddhist imagery but his style is based on the works of famous Ukiyo-e artists from the Edo period (1603-1867), most notably Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861), Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) and Kawanabe Kyosai (1831-1889). Woodblock artists were in fact largely responsible for the flourishing of irezumi during the Edo period. Irezumi have had an oscillating respectability through Japanese history. While their origins several thousand years ago were likely ritualistic, protective and decorative, as in other cultures they were later used to identify criminals. In the Edo period, katana (samurai swords) were the exclusive pride and possession of a warrior class in which hara-kiri (ritual suicide) was a part of the chauvinistic code and the ideal was a certain purity. There was fervent demand among commoners for tattoos as a kind of correspondent to those warrior blades. Kuniyoshi’s stunning illustrations of the popular Chinese literary classic Suikoden created quite a stir and the demand for imitative tattoos just exploded. In the Meiji period, however, the oligarchy saw tattoos as barbaric and outlawed them to improve Japan’s image in the West. While U.S. occupation authorities legalized tattoos again in 1945, the art has retained its wide associations with the criminal underworld. True, tattoos are becoming more widely accepted in Japan. Horimyo, however, doesn’t believe that the spread of small, whimsical fashion tattoos will necessarily restore the spirituality or respectability of tattoos. He continues to believe that the spiritual significance of tattoos is their most important attribute. Since the Meiji period, Japan has been flooded with Western culture. After wartime defeat, it was colonially occupied by America, further inundated with Western culture, and even in the tattoo world, Western tattoo machines became common. Horimyo professes to believing that the style of tattooing by hand that developed independently in Japan is a source of Japanese pride, an important relic of traditional Japanese culture and a key to renewal. It is the spirituality and significance reaching back to the origins of irezumi that Horimyo would like to restore. Horimyo’s devotion is paying off. He has won several international awards for his work, he is being featured in media around the world, and his popularity is growing. But enlisting Horimyo’s services is not so simple. He does not work in your regular business-oriented tattoo studio and does not use that style; he still relies on the traditional Japanese technique of inking by hand that has very few seekers. He generally only works on one client a day and neither directly advertises nor promotes his work. His clients have all come to him through introductions. He refuses, albeit politely, some seekers. Most of his clients are male. Any individual, however, who has a genuine and passionate desire to get a tattoo by hand (and who also establishes a connection with Horimyo) can find ‘a way’ to make the dream real. And also permanent. |

彫妙氏は溌剌とした鋭い眼差しで握手を求めてきた。表情には自信とパワーが溢れている。その表情からは彼の心の中にある目的意識のようなもの(彼はそれを「道」と呼んでいる)がはっきりと見て取れた。

この若き刺青師がこれまで歩んできた道は平坦ではなかった。10代の終わり頃、当時の仲間達の影響でギャングスタイルからチカーノ・カルチャーに興味を抱いたのが事の始まりだという。「とことん追い詰めて、生のチカーノ・カルチャーを学ぼうと19歳で単身渡米し、その後メキシコまで渡ったのですが、凄まじい貧困という現実を目の当たりにし、又、L.A.でも貧困の為ギャング達はたった10ドルで人を殺すのを知り、自分は日本人なんだという事を深く再認識し、日本みたいに豊かな国でチカーノスタイルやギャングスタイルを真似るのは、リアルではなくフェイクであると深く気付かされました。では一体、日本人の俺にとってリアルなスタイルとは?と考えさせられ、他国の人達が持つ愛国心や誇りというものの大切さにも気付かされました。敗戦後、愛国心も誇りもなくしてしまった日本で、俺にとって日本人としてリアルであり誇りとなるものは、世界中で最高の評価と賞賛を受ける日本伝統刺青であると気付き、それを同世代の人達に伝えたい!とメキシコの国境沿いの町で思わされました。」そしてそこからが長くて険しい「道」の始まりだった。 帰国後は当時、上下関係の厳しい刺青の世界と自由を求める彼のライフスタイルの違いや、貧困国への国際貢献の道などで、なかなか刺青師になる決意がつかず、未来への道を悩み求め、さまよう日々が続いた。だがある日、友人に一冊の本を見せられ、 「刺青と同じくらい古い歴史を持つメンディー(ヘナタトゥー)が、マドンナのPVなどの影響もあり、アメリカ西海岸を中心に流行しだしている。」という記事を見て、これだ!!と直感し、ロサンゼルスに渡った。彼はそこでヘナ・タトゥーと呼ばれる二、三週間で消えるナチュラルで伝統的なボディーペイントを、著名なアーティストより学んだ。そして帰国の飛行機の中である人物に出会った。隣に座っていたその人物は、後に彫妙氏の頭部に昇龍の刺青を彫ることになる刺青師だった。彼の紹介で、彫妙氏は何人かの刺青関係の仲間、数名の刺青師達と出会うことが出来、やがて神奈川の総手彫刺青師の下で修業を始める事になり、三年間の修行を終え、約六年半前に独立した。客はいわゆるその筋の人たちではなく、あくまでも個人的な理由で刺青を入れたいという人に限定した。彫師としての名前にもこだわった。機械を一切使わないという総手彫に対するこだわりと、仏教の妙法へのこだわりを名にして「彫妙」とした。「妙」という字は、彼にとって人生の中心的な精神の支えであり、彼の刺青を背負う人達が、世界に誇る日本の伝統文化を身体に刻む事により、日本人としての誇りを持ち、人生を前向きに生きていってもらいたいという想いで、彫妙という旗を上げた。 実際墨を入れ始める前に、まず彼は客と十分に打ち合わせをし、墨を入れる当日には、瞑想と祈りの時間をとる。彼が施す刺青には仏教的なイメージのものもあるが、歌川国芳、葛飾北斎、河鍋暁斎らの作品に代表される江戸時代の浮世絵が基本になっている。実際、江戸時代の刺青の流行は当時の浮世絵師たちの影響が大きかった。

日本の歴史において刺青の意味合いや社会的地位はさまざまに変化してきた。数千年前とされるその起源において、おそらく儀式的、守護的、そして装飾的な意味が始まりであったが、その後は他国の文化にも見られるように刑罰の一部を意味するようになった。そして、江戸時代においては、武士が刀を自らの誇りとし、切腹を男気的なけじめ、潔さとするのに対し、庶民も武士の刀に対当するものとして刺青を熱く求め、歌川国芳の水滸伝の影響で、刺青は一気に隆盛を極める!しかし、明治に入ると政府は刺青を野蛮なものと見なし、西洋から見た日本のイメージアップを目的として、刺青を法律により本格的に禁止した。1945年には米軍により合法とされたが、今日に至るまで闇世界とのつながりは根強く残っている。 日本において刺青が以前よりも社会的地位を認められてきているのも事実である。しかし彫妙氏は、気軽なファッションとしての刺青の流行が、刺青の本来持っている精神性や本質的な価値を向上させるとは考えていない。彼は刺青において最も重要な事は、精神性と価値だと考える。日本は明治時代より西洋の文化が強く入り込み、更に敗戦によりアメリカの植民地的な国になり、西洋文化に侵略され、刺青界でも西洋から来たマシーン彫が主流となってしまった。日本が独自に生み出した総手彫の刺青こそ、日本人としての誇りであり、伝統文化の生き残りであり、復興への手掛かりになるものであり、刺青の本来持っている精神性や本質的な価値を向上させるものだと彫妙氏は考えている。

彼の努力は報われつつあり、彼の作品が海外で賞を受賞したり、世界中のマスメディアが彼を取りあげたりして、人気は高まってきている。 彫妙氏に刺青をお願いするのは簡単なことではない。彼は現代の一般的で商業的なタトゥーアーティスト、タトゥースタジオのスタイルではなく、非常に継承者が少なくなってしまった日本の伝統技術である総手彫の技法にこだわり、基本は一日に一人だけを彫り、一切広告や宣伝をせず、完全紹介制によってのみ客を取っている。客の依頼を丁重にお断りすることもあるという。客の多くは男性だが、彫妙氏との縁と熱く純粋な気持ちで総手彫の刺青を入れたいという願いを持った人ならば、誰でもその願いを叶えられる。そして叶えられた願いはいつまでも消えないだろう。 |

彫妙のウェブサイト(Horimyo’s website): www.13project.com

Order a copy of Koe #2 to view the centerfold photo spread by Will Robb. Online photo gallery coming soon!

[…] See feature in Koe Magazine http://www.koemagazine.com/2009/05/horimyo/ […]